Just enough coding, pt. 2 - Basic code anatomy

Welcome to part 2 of my “Just enough coding” blog series that tries to provide a super high level view of programming aimed at lay people; just enough so that you have a basic understanding of some concepts to talk to your programmer friends / coworkers / partners.

0. previously…

… we looked at what programs and processes from a user perspective are, and how they interact with an operating system. In this entry I want to go a very basic example of what the source code of a program looks like.

1. What even is “source code”?

Let’s talk about the most important abstraction of programming: Source code.

1.0 WAIT, what does “abstraction” mean (in this context)?

Before going any further, we need to clear up a pretty important word / concept called “abstraction”. You may know what “abstract” is, and Merriam-Webster lists (at the time of writing this) four different definitions + sub definitions. Some noteworthy ones are:

- “disassociated from any specific instance” or “difficult to understand"

- "having only intrinsic form with little or no attempt at pictorial representation or narrative content”

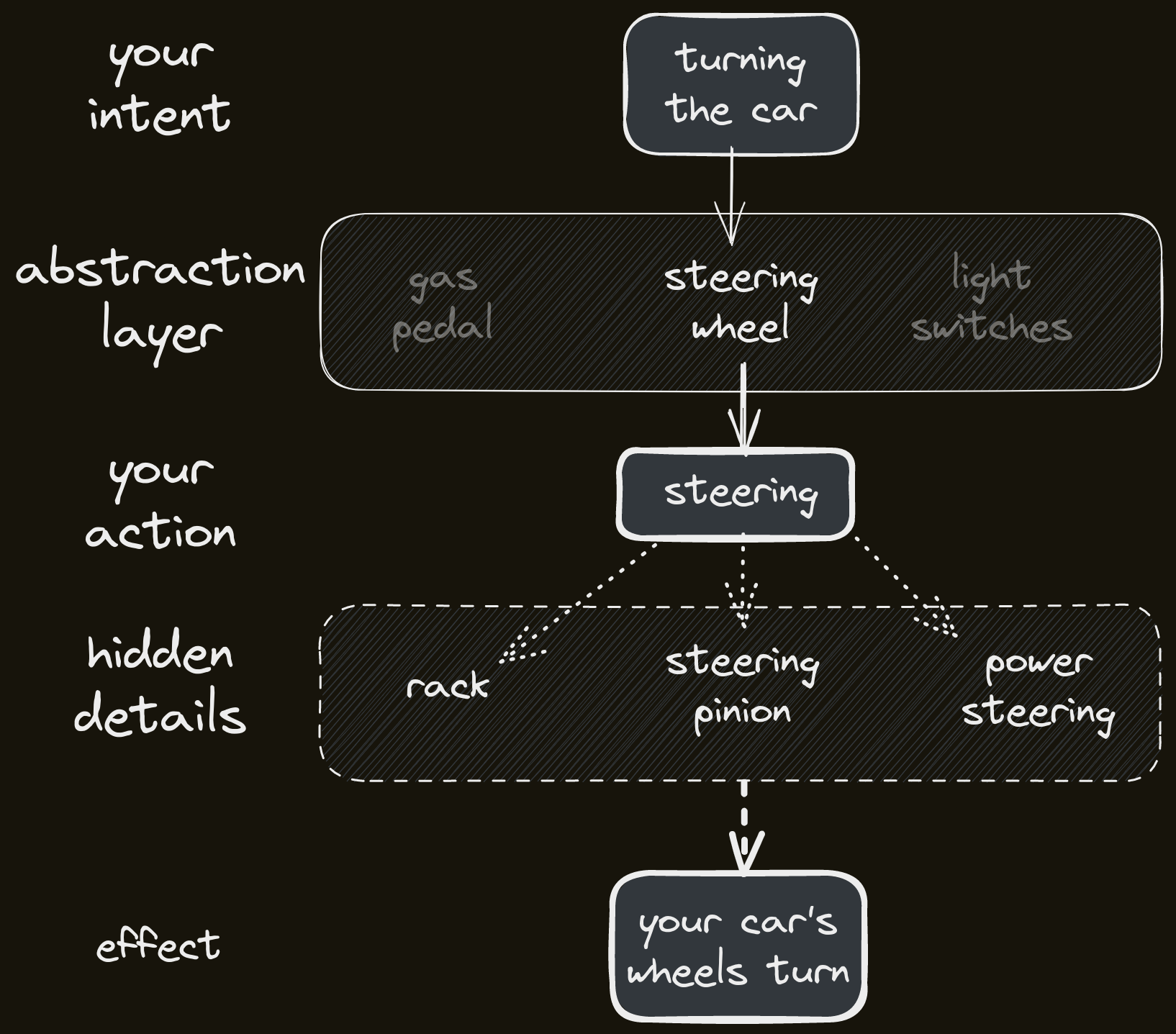

I think this covers what most people have in their minds when they hear the word “abstract”. But, though I don’t know where it came from, when programmers talk about “abstraction”, what they often mean to describe is something that hides some details to make something easier to use. Basically, an abstraction is sort of a layer (and you may often hear about “layers of abstraction”) that makes something easier to perform a certain task.

The best real-world example I came up with so far is steering a car. When you turn the steering wheel of a car, there is a BUNCH of things happening to make your wheels turn. The steering wheel itself is sort of an abstraction for turning the wheels. You don’t have to think about all the intricate mechanisms that are necessary for that process, all you need to do is turn the wheel.

Similarly with pushing the gas pedal to accelerate, or hitting the breaks, and so on. There is an easy interface to operate the car, where, apart from some incredibly rare edge cases, you don’t have to think about what’s happening under the hood.

All of these are layers of abstraction.

In programming, “abstraction” is used very similarly, where we want to give an easy-to-use interface to a user or to another developer, that may be restricted in terms of what exactly you can do with that interface (just like the “interface” of your car also limits the things you can do with it), but makes it ultimately easier to understand and use.

1.1 Machine readable vs human readable

”Source code” is probably the most important layer of abstraction in programming. A computer operates purely on manipulating ones and zeros and that doesn’t exactly scream “easy-to-use”. So instead, people came up with the idea of a “programming language” to abstract away all those details and instead work with what we would call “human readable” code, whereas the ones and zeros are called “machine readable”.

When you write a program with source code, and you want to to execute that program, you need to turn this human-readable code into machine-readable code. The overarching process to achieving that is called “compiling”, and we (often) use programs called “compilers” to do that job for us.

As you will see, there are a lot of different programming languages out there, but they all have certain similarities. Think of it like the european languages, most of which can trace their origins back to languages like ancient latin, where learning a “latin-influenced” language becomes progressively easier the more similar languages you already know. In that sense, most programming languages have similar constructs and syntax, so that the hardest language is always your first one; it only gets easier after that.

1.2 Machine instructions

There also are, in a sense, machine languages, which are instruction sets directly implemented into a chip. The most low-level of languages (low-level meaning as close to the hardware as possible) still used today, though very sparingly, are called assembly languages, and they are specific to the architecture of the chip. For example, most Windows machines run on the so called “x86_64” architecture, whereas you have probably witnessed the hype about Apple’s M1 chips, which are based on the “ARM” architecture. These two families of chips indeed speak different languages and have different instruction sets.

For some Apple users this fact became painfully obvious, when some of their favourite software needed to be “emulated” after transitioning to an M1 machine, breaking some of that software. In this context, “emulating” means that those programs were compiled for the pre-M1 chips, which, as I mentioned, have different instruction sets as the new chips. An emulator basically tries to make that program think it is running on the older chip by translating its instructions into the M1 instruction set.

2. The classic “Hello world!” program

When someone starts learning to code, one of the first things they learn is writing a “Hello world!” program. An important tool when writing programs is a so called “terminal”, or “terminal emulator”, which is a small program to issue commands to. Some windows users might know the “Command prompt”, Mac users typically use “iTerm”.

If you ever use these, and even issueing a simple command makes you feel like a hacker, you are not alone, by the way. The more complex your commmands, the more you feel like one, and that feeling never goes away.

Original source: Kung Fury; http://www.kungfury.com/

The reason terminals are used is that they are incredibly simple, and writing programs that you just run from a terminal and that prints text to that terminal, is very simple as well.

A “Hello world!” program is a program that does nothing but print the text “Hello world!”, usually to one of those terminals that you called the program from. In this section we want to look at a small example for these sorts of programs to see how source code can look like.

2.1 “Hello world!”, written in C

Let’s look at an example in one of the oldest languages still in use today, C, and we will slowly take apart what this program consists of:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello world!");

return 0;

}

One thing that hopefully jumps at you right away is the line printf("Hello world!");.

This is the bit that prints that text, but… why and how?

2.2 Functions and printf

First of all, printf is what we call a function.

You may remember functions from math class, like f(x) = 2*x, which is a function called f that takes an argument x, and returns the result of 2*x.

In programming, a function is similar, where it may take arguments, perform some instructions, and may return a result.

Those instructions are usually just other pieces of code, and the main use of functions is separating certain tasks from one another, giving those tasks descriptive names, and abstracting away the details of what the function does while providing an easy-to-use interface.

printf does exactly that: Under the hood, there are bunch of complicated instructions happening, but the only important bit for us is that it makes text appear on the screen.

Like functions in math, many (but not all) programming languages want their arguments handed to them as a list surrounded by parentheses.

Here, printf wants you to hand it a piece of text, often called a “string”.

Since we use text to write our code, we need a way to separate literal text from our code, and to do that most languages use quotation marks, which is why the Hello world! in that example is surrounded by them.

2.3 main()

Next, let’s talk about this line: int main() {.

This is what we call a function definition.

This particular function is called main, though, at least here, it does not take any arguments (note the empty parentheses), unlike printf which wants you to give it a string.

Most functions “return” something, they have some sort of result, like the math function f(x) = 2*x, which returns the value of 2*x.

The keyword int tells us that function main returns an integer (int just being short for, you guessed it, “integer”).

Defining what “type” of value of a function returns is very useful, though we won’t dive into that yet.

For now, all we need to know, is that the function main returns a whole number, i.e. an integer.

You have, without a doubt, noticed the curly braces { and }.

They fence in the content of our function definition.

Basically, everything inside of those curly braces is the set of instructions that we want to have performed, whenever the main function is called / executed.

We often call each step of a function a “statement”, and in C (and the many languages that were derived from it), we end a statement with a semi-colon, similar to how we end sentences with a dot.

We can see that the main function consists of two statements, read from top to bottom:

printf("Hello world!");

return 0;

The first statement we already discussed; it is a call to the printf function that will print the text “Hello world!” to the screen.

The next statement is a special statement that tells us the return value of the function, and then it terminates the function call.

Basically, if we were to call main, it would first print “Hello world!”, and then hand us back an integer with the value 0;

We will talk about this value in just a second.

Now, the main function is special.

Earlier we talked about how source code needs to be translated to machine instructions, and we called that process “compiling”.

Most languages have something similar to a main function that you need to define the contents of, because that’s the starting point of your program.

In a way, the compiler, the program that does the compiling, looks for this main function and it will complain if it cannot find it in your source code.

When it compiles your program, it goes through the statements inside of the main function top to bottom and translates them to machine code.

You can really think of programs as a list of instructions that way.

2.4 The #include directive

There was another line in the code snippet up top: #include <stdio.h>.

The short and sweet explanation for this line is that the printf function isn’t always available to the compiler.

Instead, we need to tell it to read a different file, evaluate the contents of that file, and sort of “add” it to our program.

The file stdio.h contains the definition for printf, so that’s what we need the compiler to “include” into our program so that it knows what printf means.

Without this line, the compiler would complain that our main function wants to call a function called printf, but it simply doesn’t know that function.

2.5 The return value

If you’ve read the first part of this blog series, you might remember that we talked about something called “exit codes”, which are numbers that a program returns to the operating system to tell it whether the program ran successfully or not. You may also remember that, when a function “returns” the number “0”, this tells the OS that the program run without any issues.

As I mentioned, the main function is the starting point of a programs execution, and, likewise, it is also where a program’s execution ends.

In every regular C program, all that really happens is that the main function read top to bottom, but it may contain many different other function calls that may run for a long time; or even indefinitely until the program is halted.

The return statement of the main function thus tells us which exit code to hand back to the operating system after every other instruction in our program has been executed.

This is works very similarly in most programming languages in use today.

Maybe you have already put it together at this point, but the reason the return value of main is “0”, is because, if our program reached this line during execution, we want main (and with that our program) to end and return “0”, indicating to the operation system that our program ran successfully.

Conclusion

This was a rather dense blog entry, and we covered a lot of ground to acquire some very fundamental knowledge. We talked about abstractions, programming and machine languages, and even looked at our first little example of what a program in source code form looks like. If you have reached this point of the post, you can probably pat yourself on the back, because these things tend to be a bit alien to people not already used to them. Most importantly, I hope you learned something!